DIVINING INTENT:

A Look at Japan’s Toxic Waste Trade Policy and its JPEPA implication

By: Richard Gutierrez, J.D. Ll.M.

Basel Action Network, Asia-Pacific

Participant, Magkaisa Junk JPEPA Coalition

Last May 22 and 23, 2007, an exchange of diplomatic notes occurred between Philippine Foreign Secretary Alberto Romulo and his Japanese counterpart Minister Taro Aso. The exchange of notes was prompted by “doubting Thomases”, according to Philippine Ambassador to Japan Mr. Domingo Siazon, Jr., “who have to see Jesus Christ in person alive before they believe. In order to cover that, we [Philippines and Japan] will have a side letter.”1 The diplomatic notes reiterate Japan’s promise not to export toxic wastes to the Philippines, unless prohibited by Philippine or Japanese law, and in accordance with the Basel Convention on the Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal.

The diplomatic notes were issued in conjunction with the Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement (JPEPA), which was signed by then Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi of Japan, and President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo of the Philippines on September 9, 2006. Japan’s Diet ratified the agreement last December 6, 2006, and is awaiting ratification of the Philippine Senate.

In spite of the exchange of notes, Philippine civil society groups were back on June 4, 2007, at the opening of the last few sessions of the Senate of the 13th Congress of the Philippines. The organizations present, expressed their concerns over Japan’s promise contained in the notes, questioned the legal nature of the notes, and renewed their call for the country to ratify the Basel Ban Amendment and for the Senate to thoroughly study the JPEPA. Why do these “Doubting Thomases” continue?

Diplomatic Notes

It does not help that the copy of the exchange of notes has not yet been released by the Department of Foreign Affairs. But more pointedly, at the least, the exchange of notes appear to be premature since the JPEPA has not yet been ratified by the Senate, as opined by some Filipino international law experts. Without a main agreement for it to be linked to, what is the exchange of notes for? Assuming it is a stand alone agreement, what new obligations are created, how will these be enforced, and when does the agreement take effect?

According the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in the exchange of notes, it is expressed that Japan would not be exporting toxic wastes to the Philippines, as defined and prohibited under the laws of Japan and the Philippines, in accordance with the Basel Convention. There’s nothing new here, and merely repeats the fact that export control obligations are already embodied in the Basel Convention and, as mentioned, Japanese and Philippine laws.

Since the legal nature of the notes is ambiguous at this point, and that no new obligations are established, it appears that for all intents and purposes, the exchange of diplomatic notes merely is a statement of Japanese intent, at present.

Divining Japanese Intent on Toxic Waste Exports

There is a disconnect between what Japan says in the notes, and from their actions the past years on toxic waste exports. Below are glaring points that highlight Japanese intent beyond the press releases and notes they issue.

1. Japan has been an opponent of the Basel Ban Amendment, a prohibition on all rich countries for exporting their toxic wastes to poorer countries, for whatever reason. Japan’s opposition against the Amendment runs far back, when the Amendment was being pushed by developing countries in the early ‘90s. A recent example of Japanese opposition against the Basel Ban was in August 2006, when the Japanese government sought a consultancy to prepare an assessment on the use of bilateral agreements “for bidirectional movement of toxic wastes between Japan and Asia.”

2. Japan has also funded another group the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), a policy think-tank, who developed a policy paper decrying the Basel Convention as a “cumbersome procedure” that has “become a barrier to international trade of recyclables”.2 The IGES proposed expansion of cross-border transfer of recyclable toxic wastes through the use of the 3R Initiative and through bilateral Free Trade Agreements, such as the JPEPA.

3. At the most recent Conference of the Parties of the Basel Convention in Nairobi, Kenya in 2006 the Japanese government representative was asked in a side event whether or not they supported export of hazardous electronic wastes to developing countries from Japan. They replied in the affirmative. Further, Japan was the only Party taking the floor during the meeting to denounce the Basel Ban Amendment as being unacceptable to Japan.

4. BAN has conducted field investigations in China (2001) and Nigeria (2005) and found evidence of toxic Japanese e-waste being dumped in the guise of “second-hand” goods in these countries, in violation of local prohibitions against these toxic wastes.3

5. Japan has led efforts on behalf of the powerful global shipping industry in arguing strenuously that the Basel Convention should not apply to ships at end-of-life.4 Japan took a lead role in past Basel Convention meetings in blocking any efforts the Basel parties were willing to take toward tightening up the Basel regime with respect to dealing with ships.5

Recommendations

Civil society groups are unsatisfied, even concerned, with the exchange of notes on JPEPA. In their plea to the Senate last June 4, they recommended the following actions, which are restated here:

1. Ratification of the Basel Ban Amendment. The issue of toxic waste imports into the Philippines will continue to shadow any trade pact, as long as global generation of hazardous wastes continues to rise and the disparity between developed and developing countries widen. The Basel Ban Amendment offers a strong first line of defense for the Philippines and other developing countries, by shifting the onus of preventing the exports to toxic waste generators, such as Japan.

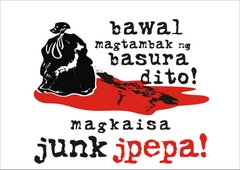

2. Junking of JPEPA. Aside from toxic wastes, the JPEPA contains other “toxic” and exploitative provisions. This symptomatic of the objectionable and undemocratic process that the government utilized in negotiating and drafting the JPEPA.

3. Addressing broader concerns raised in the JPEPA through robust and transparent hearings in the Senate. Concerns from farmers, fisher folk, indigenous communities, local businesses, laborers, migrant workers, healthcare workers, and other stakeholders have not been fully heard. A decision promoting the interest of the Filipinos can only be arrived at once all stakeholders’ concerns are heard and considered.

- END -

________________________

Notes:

[1] Philippine Daily Inquirer, “RP,

[2] See at: http://www.ban.org/Library/JPEPA_Report.pdf.

[3] BAN’s

[4] End-of-life vessels contain various toxins, e.g. asbestos, Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), etc. that render them hazardous wastes under the Basel Convention.

[5] To learn more about this issue in the IMO and efforts to drive it away from

No comments:

Post a Comment